Based on the 2001 novel by Philip Reeve, Mortal Engines is set in a post-apocalyptic future in which entire cities are on wheels, cruising the wasteland and raiding the scraps of the old world for resources to scavenge. The film possesses a striking visual style which is brought to life by director Christian Rivers, who has worked on visual effects for Peter Jackson since before his Lord of the Rings days.

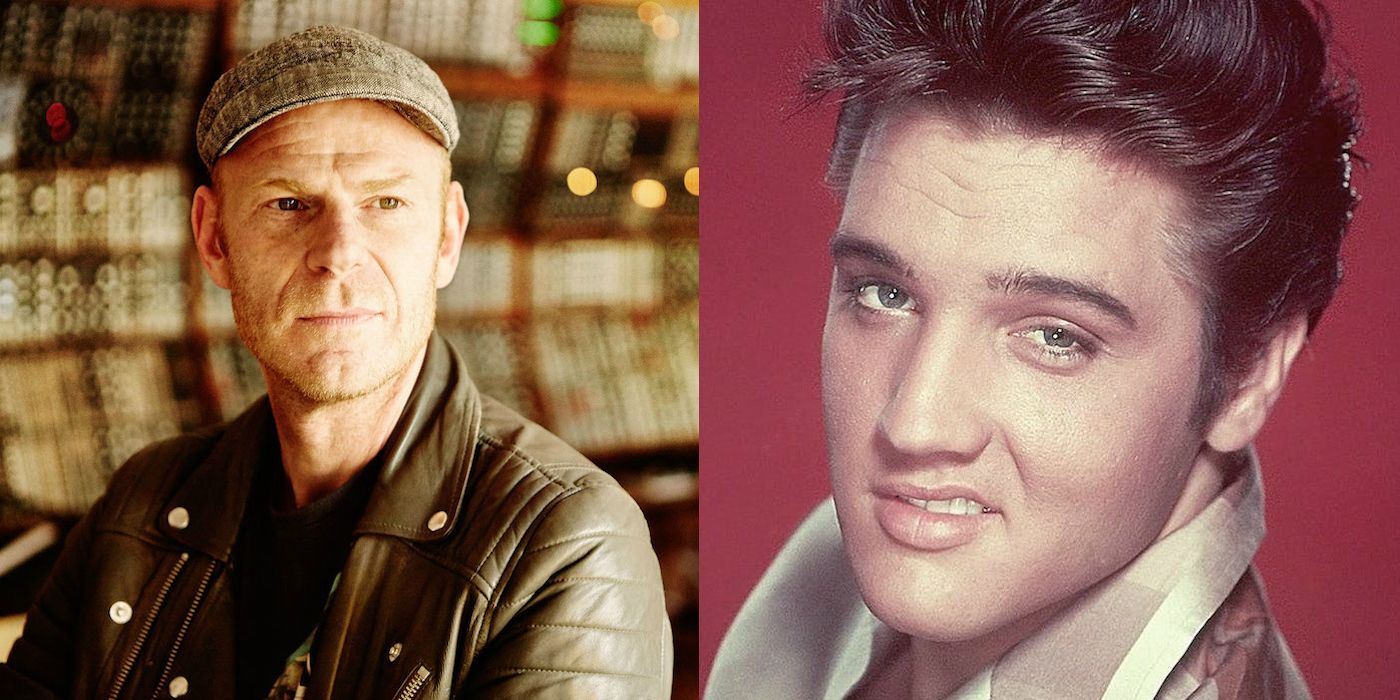

The film's score is provided by Tom Holkenborg, better known by his stage name, Junkie XL. A lifelong musician, the 51-year-old composer made a name for himself as a DJ and producer before exploding in popularity with his 2002 remix of Elvis Presley's "A Little Less Conversation," which became an international #1 hit, 25 years after Elvis' death in 1977.

Related: Hugo Weaving & Stephen Lang Interview – Mortal Engines

These days, Holkenborg is an accomplished film composer, with a healthy roster of big-name blockbusters under his belt, including Mad Max: Fury Road, Deadpool, and Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice. Mortal Engines is his latest blockbuster film score, and he's showing no signs of slowing down, since his work will be featured in 2019's Alita: Battle Angel.

Holkenborg spoke with us about his life and career, from his early days as a mixing engineer in Holland to working with some of the biggest directors in Hollywood, as well as sharing the awkward true story of why he's credited as "JXL" on his Elvis Presley recording. He talks about collaborating with Hans Zimmer on the score to Batman v Superman, and explains the creative difference between composing for albums, films, and video games.

Mortal Engines hits theaters on December 14; in the meantime, check out Screen Rant's exclusive new piece of music from the film's original score!

How did you get involved with Mortal Engines?

It started with the script that I was sent to see if I was interested. I read the script, and I immediately called the producer back, saying, "I'd love to be involved with this movie." And he said, "Okay, let me discuss with Peter (Jackson), Fran (Walsh), and Christian (Rivers, the director)." A week later, I was in London, recording Tomb Raider, and I got a phone call with all of them, we talked a little bit about the film. They said, "Well, you have to see it; it's hard to explain over the phone." I said, "Sure, fly me to New Zealand, I'll be there!" The next week, I was in New Zealand, hanging out with them and watching the movie. Had a really nice dinner at somebody's house with some really good wines... They take their time over there! We really clicked on a personal level. I was there for six or eight days, just hanging out, watching the movie, talking about it. After that, they said, "Okay, you're hired. Let's start!" That was October of last year. So basically, from October, all the way to July, I've been going back and forth to New Zealand, playing music, adjusting music, and eventually recorded it there, with the New Zealand Orchestra. It was just a mind-blowing experience to work with filmmakers of this level. I mean, little did I know... In 2003, I came to L.A. wanting to be a film composer. Now, 15 years later, I've collaborated with Peter Jackson, George Miller, Tim Miller, Zack Snyder, James Cameron, Robert Rodriguez. It's amazing.

I think a lot of people take film scores for granted. They don't really notice it unless you take it away or point it out. Tell me a little bit about the process of getting a scene that has no music, it might have a temp track. It might not even have any sound effects, and having the job of making it work.

That's a complicated question that calls for a complicated answer, but let me try to boil it down into something that's understandable for people who are not part of this scene. I work usually with directors who do not work with a temp score. That's one thing which can be a major relief. Secondly, I usually write a lot of music beforehand, before they even start editing the movie. So they're now using my music to cut the movie. That makes it a bit easier, too. But there's a lot of scenes always left that have no music, no sound effects. Sometimes the dialogue is taken out, because they'll want to replace the dialogue with something else. And you just basically look at the scene. I'm just gonna say something generally, not particularly for any movie, but as an example, you have a scene for the good guy, a scene for the bad guy, and a scene for the kid. And then you have a scene where the good guy is having dinner with the kid, and the bad guy comes in and threatens to kill the kid if the good guy doesn't do what the bad guy says. Now you have a scene with three characters, and you have three different themes. You start playing around with tempo; is this a fast scene? Is it a slow scene? At what moment does the music need to shift? All these things are important to consider before you start making the music, but then the director has very specific ideas about that, too. So I usually come up with a first draft of what I think it needs to be, and then you go back and forth with the director until the scene is done.

A lot of people are comparing Mortal Engines with Mad Max, saying "It's Peter Jackson's Mad Max," or "It's Mad Max meets YA." I don't know if that's true or fair, but you did the music for both Mortal Engines and Max Max: Fury Road. Did you have those comparisons in mind when you were scoring Mortal Engines?

For me, what is similar is that they're set in really crazy worlds that we do not live in, and both movies have very creative vehicles. But for me, that's where the similarities end. The idea with Mad Max was that it was about this crazy world and roller coaster chase to take out Immortan Joe. But even more so, the focusing on the human side of the characters is kept to a minimum. It's only in the middle of the film, where Furiosa finds that the promised land she wanted to go to is no longer there, and many of the people she loved and grew up with are no longer there, but that's a very short section of the film. The job description that I got from George Miller was, "you have to score how aggressive that world is, how cold, psychotic and crazy it is, and do it over-the-top," and that's what I did. The majority of the music is exactly that. With Mortal Engines, we also live in a crazy world, but what is more important than living in the crazy world is the story of Hester: who she is, where she comes from, why she wants to be on the London, why she wants to kill Valentine, what happened to her in the past, and what is happening to her in the future. My job description was very much, "make sure that we feel the emotional ride of the main character, Hester, throughout the film. Yes, focus on the outside worlds and the craziness of the worlds in the score when it's appropriate, but focus at all times on what Hester is, what she wants, and what she's looking for." That means that in big action scenes, sometimes the music is very small because it just follows her, and that's a big difference in approach. I would say that's the big difference between the two movies.

You moved to L.A. to become a film composer. Can you tell me a bit about composing for film, as opposed to being a DJ and producer? I mean, you've been a multi-instrumentalist since you were a child, and music is music, but was there a transition that needed to be made? Extra studies you needed to practice?

Yeah, absolutely. I call myself a "full contact composer." Everything starts with an instrument. I need to hold instruments. I need to turn knobs. I need to bang on drums. I need to play guitar. I need to play violin. I need to be a full contact instrumentalist. That's how I write. I'm not the type of guy who sits behind the piano with a notebook, drawing notes on a piece of paper and then it gets played by an orchestra; that's not how I work. First, I was a mixing engineer producer before I became an artist. That was my first career. I started when I was 13 or 14, interning in a studio, and I eventually became an engineer/producer. At some point, I was producing all these bands in Holland, but also from the US and from England. That was a solid career. By the time I was 19 or 20, I started making music myself, and I was playing in industrial bands, and then in the 90s, I became Junkie XL. I started doing a lot of video games, as well. I moved to L.A. to become a film composer, but I had already done many video games. Then I started doing movies. All three elements require a whole different skill set of how to make music. You're completely right, it's music and the end of the day, no matter what, but the disciplines are very different.

As an artist, you can typically do whatever you want. You can release a CD and that's the end of them. With the video games, you're talking with one or two people that are called the "creatives," and they will guide you through what they feel the game needs, musically. For film, you go to the theater, you watch the thing from beginning to end, and you leave. For video games, not so much! You sit down, you start playing the game, and if you're good, you might get to a certain level after eight hours, ten hours, fifteen hours, and the music needs to interact with the player. If they do something great, the music will be great. If the player gets killed, the kill music happens. If something emotional happens, you'll hear emotional music. It's constantly interacting. But the amount of feedback you get from a video game company is less precise and less intense than with movies. With movies, like Mortal Engines, you work with the creative team, Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh, and Christian Rivers, filmmakers at the highest level you can potentially work with. They're very critical, they want to get the best out of you, and the feedback process is more intense than any video game that I've ever done in the past. The music, obviously, is a horizontal experience. With movies, you write a music arc over the course of two hours: how does the theme begin, how does the theme develop, when does it become big and heroic, when does it become small? It's a way more complicated process, I would say, than any of the other disciplines. An artist can release an EP with four tracks on it, about twenty minutes. I was sometimes able to finish twenty minutes in a week and release it as an EP. Twenty minutes of film score isn't going to be finished in a week! You're going back and forth multiple-multiple-multiple-multiple times before you record it, and even after that, you still have to make changes. It's a way more intense process. I hope that explains it a little bit!

You've done a lot of movies. I imagine there are some where you perform the score yourself, as opposed to working with an orchestra, is that right?

It depends. I'd say, every movie that I've done, you go in recording a version of the orchestra. With Mortal Engines, it was all-our orchestra. It was full strings, full brass, full woodwinds, a choir, solo sopranos, you name it! It was a big operation. A movie like Deadpool, which was so reliant on 80s synths and 80s craziness, we recorded some orchestra for that, but it was way less. It really depends per movie, but there's always live recording involved.

At Screen Rant, we love super hero films. You've worked on some big ones, and you worked with Hans Zimmer on The Amazing Spider-Man 2 and Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice. Something that I'm very interested in is when multiple composers collaborate on a single film. How does that work? Do you work on pieces together, or do you split it up and you're like, "this is yours, this is mine?" Do you share notes?

Everything is possible. The thing with Hans and I is we're really good friends. Hans has been an incredible mentor for me, to show me how this industry works, and to give me the ins and outs of how to become a successful film composer. I'll always be very grateful for that. Nevertheless, we are two people, from Germany and Holland, so leave it up to some crazy Europeans to come up with all the music for these blockbuster movies! But yeah, you just throw the two of us in a room and things start happening! Hans will play a little bit on a piano, and I'll grab an acoustic guitar and jam with him until we find something. Sometimes I would come with a drum beat and Hans would go, "Let's do this!" It was really a lot of playing around in one room. At a certain point, you divide the work, saying, "Why don't you take care of these cues, I'll do these couple of cues." And then, we get back together, play them back to back. Hans always has something to say about what I did, what he feels could be better, and I always have something to say about what he could do better or different. And we really get each other to a point where we would really try to push each other to the limit of "what can you do, what can I do, what can we do to make this better?" That was really what the big fun of that project was. Hans and I are both perfectionists, and we don't let it go until it's time to let it go, and that's not until the moment we send out the files to the studios.

While we're on Batman v Superman, there's that one Superman cue that I love so much. It's that western guitar, it's like an old-timey sheriff at high noon kind of vibe, with so much reverb... It's such a minimalist theme, but it's so powerful in that movie.

One of the ideas we had, Hans and I are really big on ideas. Besides the fact that we can both write some cool music, we're really big on ideas. Before we even started on the movie, we just talked for multiple nights in a row, about what instruments would be cool. A lot of these things were discussed. One of them was, like, Superman is such an American character. He's how America could see itself, as Superman. He only does good, he never does wrong, and he's super powerful. We wanted to have instruments in the score that really celebrated the true Americana feelings of Superman. That's why that theme is played on a dusty standup piano. It's a piano that could be in your aunt's house, it could be the piano that my neighbor, who is 93, it could be her piano that hasn't been played in twenty years. And it also has slide guitar elements that remind you immediately of that great Americana culture.

I want to ask you about your inspirations. Who are your inspirations when you're composing?

As an artist, I have inspirations that would come from a time period that might have nothing to do with the time period I was in at that point in my career. I remember when I was making the Junkie XL records, that I would primarily listen to The Beatles and Pink Floyd, and other stuff from the 60s and 70s. In my film scoring career, I primarily listen to classical music. At this point, I'm completely in love with Shostakovich's Symphony No. 10, and Bruckner's Symphony No. 7. And I just keep on playing them on repeat when I'm not working, and I just learn from the brilliant writing of these composers. And when I listened to Pink Floyd, I always loved their passion for sound design, to make things different. If you listen to Dark Side of the Moon, especially. And with The Beatles, it was like, this is what great songwriting is. You learn from it, even when you're working on a dance track. My inspiration never came one-to-one from a colleague in the field, if you know what I mean.

Can we talk about your transition from being a mega-producer and DJ to a film composer? For a long time, a lot of people, myself in particular, knew you best for your Elvis Presley remix, of "A Little Less Conversation." I'm a huge Elvis fan, and it was really cool, when I was a young teen, for him to be hip in pop culture again. I know it was a long time ago, but can you talk a little bit about working with the Elvis estate for that?

Sure! I was working in the 2000s a lot with an ad company called Wieden+Kennedy. It was this very exclusive, high-brow ad agency that was based in Amsterdam, and they literally were on the same street where my studio was. We knew each other really well, we had worked together in the past, and at a certain point, somebody knocks on my door, walks inside, and says, "Tom, I've got something, but we don't know what to do with the music." He plays me this world championship soccer commercial for NIKE directed by Terry Gilliam. It's a five-minute movie where you see all the star soccer players play games with one another in the belly of a ship. The commercial was called, "The Secret Tournament." They were looking for music, and they tried a few different things. They said, "There's this Elvis track, 'A Little Less Conversation,' and I said, 'Oh, I know that song.'" But they said, "It's too short, it's only a minute and twenty seconds, it doesn't work. We need five minutes." I said, "I can make this work. Give me a couple of days or a week and I'll come back to you." He said, "You don't have a couple of days or a week, I need this in five hours." And I said, "Well, just give me five hours (laughs)." So he left, and at that point in time, I was producing the first artist record of the UK-based DJ called Sasha. At this point in time, he was the biggest thing on the planet. So he came in and he said, "What are you doing?" I said, "I've gotta spend four or five hours on this Elvis thing." So he said, "I'm gonna go get a massage and get some food, I'll be back in five hours and we can continue working." So he goes to get a massage, chill out, have some food, and I'm just working my balls off in my studio to make this track work with the commercial. I started adding Hammond organ to it, I got a female singer in there to do some background choirs. I arranged extra brass, extra drum beats... It was still very rough, but it showed very well where it was gonna go. Sasha came back, it was now 8:00 at night, and I played it for him. He smiled and looked at me and said, "This is a number one hit." I said, "Ah, you're kidding, this is just for a commercial," but he said, "No. You don't understand what I'm saying: this is a number one hit." Famous last words! So I sent it out to NIKE, and they loved it, and they started talking to the Elvis estate. They were talking with the lawyer of the Elvis estate, and he says, "We just played the track for Priscilla (Presley), and she really loved it. Tell me, who is the producer on this track?" And then the guy on the NIKE side says, "His name is Junkie XL." And it goes quiet. After half a minute, he says, "You have to be fu***** kidding me, right?"

Because, as we know, the last few years of Elvis were primarily overshadowed by his drug use, and not so much his singing performances. So we shortened it to JXL, and it went into the commercial, which ran worldwide and did really well, and then the track started living its own life, and then eventually, we decided to release it as a single. So I spent a little bit more time on it to produce it as a proper single, and that's the track most people know today. It became a number one hit in many countries.

That's such an amazing story. I had heard about the shortening of your name to JXL, but it's so funny to hear it from you! Actually, can you tell me about being credited, even in your film work, as Junkie XL instead of your proper name, Tom Holkenborg?

Actually, it's changing. Junkie XL is really a name of the past. I started my production career in 1994, 1995, under that name. I've done a lot of movies under that name, but now we're starting to weave away from it. All the future films that I do will be under my own name, Tom Holkenborg. Junkie XL, we'll just leave for what it was. You know, what I mean? It was a great time in my life, but it's time to move on to something new.

More: Read Screen Rant's Mortal Engines Review

from ScreenRant - Feed https://ift.tt/2EtwoYD

0 Comments